CHESTER SQUARE

A Social History

Boston, Chester Square – March 2011

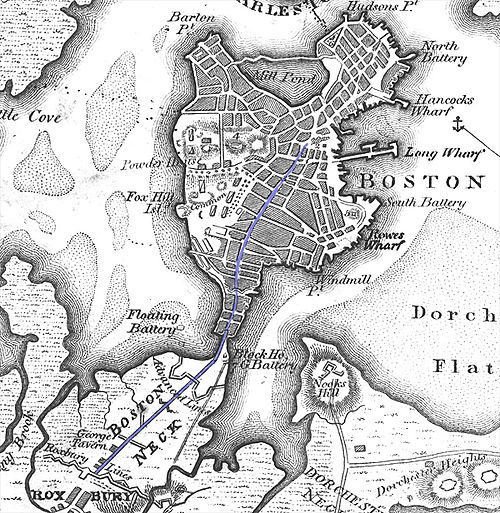

Boston’s South End, the largest preserved Victorian neighborhood in the United States today, was created in the 1840s and ’50s when a vast portion of man-made land was added to the perimeter of the city’s limits. “The Neck”, as Washington Street was known at the time, was a narrow strip one hundred feet wide that connected the downtown area to Lower Roxbury, on each side of which were large bodies of tidal marsh land.

Early-nineteenth-century map of the city of Boston, showing the two bodies of water on each side of the “Boston Neck”

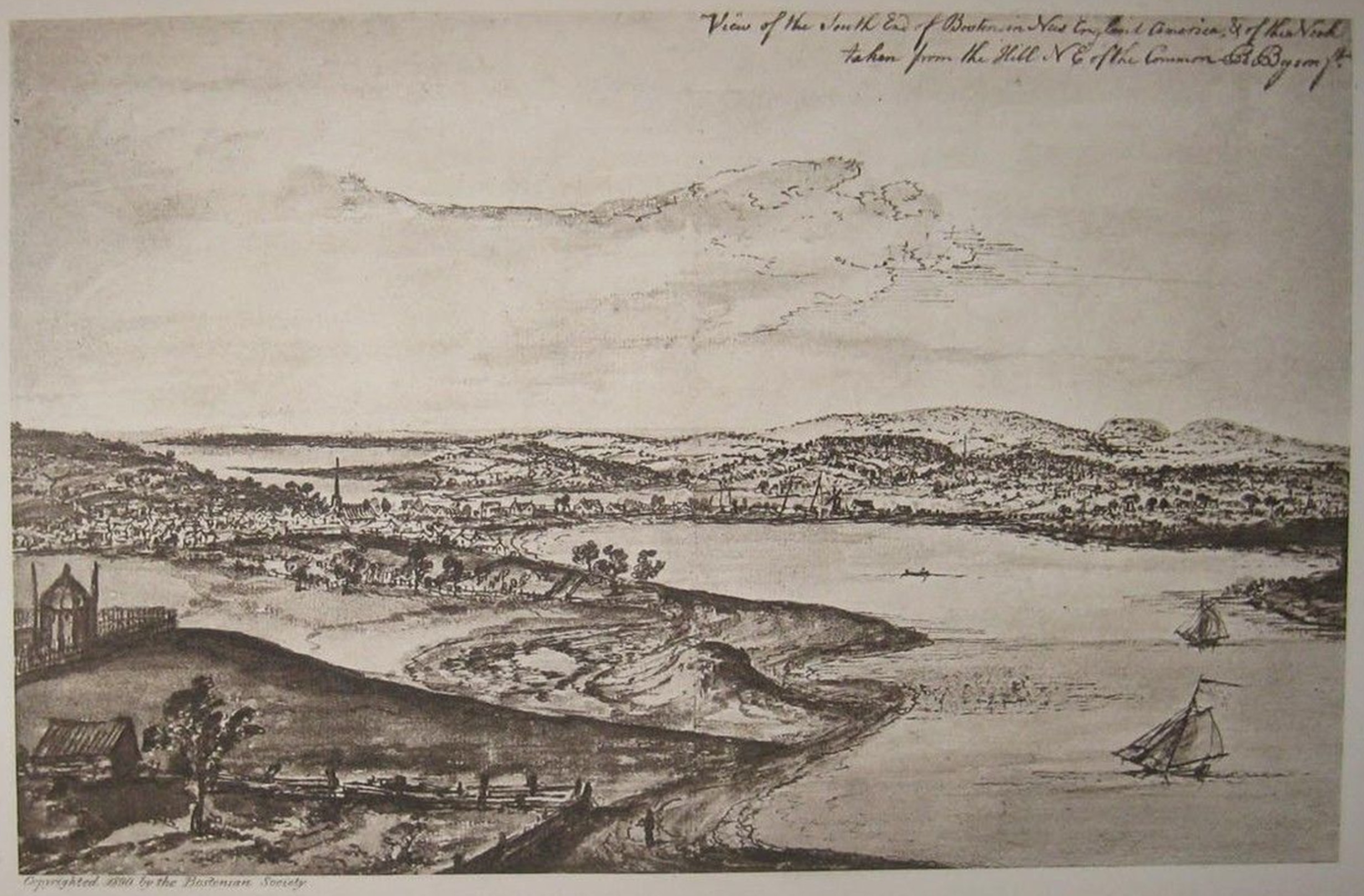

Rare 1890 engraving published by The Bostonian Society, depicting a ca. 1764 view of the Neck, and inscribed "View of South End of Boston in New England America, and of the Neck - taken from the hill North East of the Common, R. Byron f[eci]t"

(Roberto Poli, private collection)

Undertaken between the 1830s and ’70s, the filling of the Back and South Bays was a necessary step to the development of a progressing city, but not an irregular and forced one; rather, it was a natural expansion guided by both the increasing wealth of its inhabitants and the improved taste in urbanization. It was a major task, at first viewed with suspicion for its immensity. But when the project on the western side of the Neck was completed in the late 1840s, the plans laid out by skilled civil engineers lifted any doubt that the city of Boston could indeed grow in size.

Ca. 1840 Lithograph of Beacon Hill seen from Dorchester Heights, before the filling of the South Bay

(Roberto Poli, Private Collection)

To entice the emerging middle class to populate the new land, a staccato of small and large parks surrounded by brownstone single-family homes in the style of London’s urban development quickly began to appear. In 1891, the sixth edition of Boston Illustrated read:

"Boston business is rapidly expanding, and the room to do it in must expand likewise. The current is setting decidedly to the south, and year by year new advances are made in that direction, by both wholesale and retail trade. But we must speak of the existing lines of division; and for our purposes we regard at the present time as the South End, all the territory bounded on the north and west by Essex, Boylston, and Tremont streets, and the Boston and Albany Railroad, and south by the old Roxbury line. The face of the country in this part of the city is for the most part level; and a very large part of the territory was reclaimed from the sea. […] Most of the streets other than those we have named, though generally pleasant, are somewhat monotonous in their appearance. Their width and cleanness, however, and their air of quiet and repose, give a pleasing appearance to this large residence-quarter. The domestic architecture exemplifies that peculiarity of Boston houses, the “swell front,” in great variety […]. Most of the houses are of brick, in long blocks; and they are sometimes beautifully adorned with woodbine or ivy. The South-End buildings extend in solid ranks to the Providence Railroad, where they are stopped as evenly as if the rails were the waves of the deep sea."

Designed in 1850 by civil engineer Ezra Lincoln (1819-1863) and following the ideals of simplicity and good taste in urbanization proposed by architect Charles Bullfinch (1763-1844), Chester Square represented the first example of American urban development, and one of three large garden squares in the South End (the other two being Worcester Square and Union Park). Begun in October 1849, the square’s final layout was completed in May 1850, and the speculation began on October 30 of the same year, when the ninety or so large lots, averaging 2,500 square feet in size, went to auction. About two hundred and fifty people attended the event, and about half of the lots sold immediately, mostly to real estate developers. The 1851 Boston Directory was already mentioning that “Chester Square, near Northampton and Tremont streets, contains 62,000 feet of land, enclosed by an iron fence, 987 feet in length. The cost of the fence was nearly $4,000, and that of the fountain complete, about $1,000.” By the end of 1851, construction of some of the grand homes that would surround the elaborate landscaping and the three-tier fountain and fish pond had started. They were handsome, imposing, and sold quickly to some of Boston’s wealthiest families who could no longer find adequate space on crowded Beacon Hill. Most brickfront five-story residences were purchased for about $15,000; the large six-story cupolaed brownstones in the center of the square went for $21,000; and some of the more handsomely decorated, such as the two large homes on the south-east corner, sold for the astronomical price of $28,000.

Boston Illustrated recounted that Chester Square was “a favorite street for dwelling-houses. Through the avenue runs a park, narrow at the ends, but swelling out in the centre, in which are trees and flowers, with a fountain and a fish-pond, making the place a deliciously cool and pleasant spot in midsummer.”

Chester Square in the summer, ca. 1875

The lavishly landscaped garden and unusually large homes became immediately coveted by the affluent Bostonians not only for their attractiveness: the opulence of the new developing residential area was also viewed as an opportunity to showcase their prosperity. Even though only half of the lots had sold at the initial auction in 1850, many others sold within a year; and the few that had not been developed by the late 1850s were selling for three times their original amount, such had become the demand for a property on the square.

Stereograph of Chester Square ca. 1860, taken from the top floor of No. 32,

showing that some of the buildings were still under construction, and others not yet begun.

The early development of a mall on either side of the central garden, reminiscent of a Parisian boulevard and enclosed between two rows of elm trees and ornamental cast-iron fences, ensured that the homes adjacent to the two busy thoroughfares of Tremont and Washington Streets, the park’s limits, would be equally desirable. The mall extending south of the square was called East Chester Park; and the one that extended north, leading to what was later to be named Commonwealth Avenue, was called West Chester Park.

The beginning of the mall at East Chester Park, at the corner of Washington Street in a ca. 1870 photograph by J.J. Hawes .

The twin homes at 1747 and 1745 Washington Street, pictured here, are no longer extant.

(Collection of the Boston Public Library)

Stereoview of the mall leading from Washington Street to Chester Square in the summertime (ca. 1875)

(private collection)

View of Chester Square and the beginning of the East Chester Park mall in the late fall,

taken from the top floor of No. 32 (ca.1865)

Burgeoning merchants, bankers, physicians, lawyers, and religious and political figures began to reside in the large dwellings. Many of their names have been forgotten, but at the time they belonged to the most elevated stratus in the city of Boston. At No. 71, Reverend Robert Cassie Waterston (1812-1893) lived with his wife, Anna Lowell Cabot Quincy (1812-1899), and three servants. Born in Kennebunk, Maine, Robert descended from a family of cotton manufacturers. He attended the Theological School in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and became a clergyman. He was admired for his oratorical qualities. Independently wealthy, he devoted his time to poetry and writings on religious matters. He was also an avid collector of manuscripts, rare volumes, and autographs. Anna was the youngest daughter of Josiah Quincy, who had been congressman, judge of the Massachusetts Municipal Court, state representative, president of Harvard College, and mayor of the city of Boston. Her diary of 1833, which narrates social events at Harvard University and in the exclusive Brahmin society with wit and candor, offers an invaluable depiction of the American upper class in the early part of the nineteenth century.

Marble bust of Anna Cabot Lowell Quincy, ca. 1845

The Waterstons purchased the recently built home at 71 Chester Square in the spring of 1859, a few months after returning from a long trip to Europe that had begun in Paris in 1856. They had spent the winter of 1858 in Rome, eventually traveling south to explore the natural beauties of the Amalfi Coast, settling at the elegant Hotel Vittoria in Naples. It was at the beginning of their sojourn in that city that their daughter, Helen, developed a mysterious illness brought forth by the insalubrious air of the area. Quickly worsening, the family removed to a smaller hotel located farther from the coast, where she died three months later while the flaming Vesuvius lit up the evening sky. She was seventeen. The American poet and journalist William Cullen Bryant, a friend of the family, happened to be sojourning in Naples at the time and witnessed Helen’s death. In a letter to the New York Times, dated two weeks after the tragic event, he reported:

"The sewers of the city have their mouths here in the edge of the bay, and under the very windows of the houses there runs one of these foul conduits, with frequent small openings, which send up offensive exhalations. Possibly this is the main occasion of the mischief […] At length, a little before her end, her mind began to wander, but in such a manner that it seemed as if she was admitted to a glimpse of the brighter world to which she was going, and she passed away in what might almost be taken for a beatific vision – a happy life closed by a happy death – leaving her parents broken-hearted, but for the strong religious trust which supported them."

A decade earlier, while living on Beacon Hill, the couple had already lost their firstborn, Robert Cassie Jr., who at the time was a small child of two. Devastated by the loss of Helen, their only surviving child, they chose to leave the house that was the repository of too many memories, and begin anew.

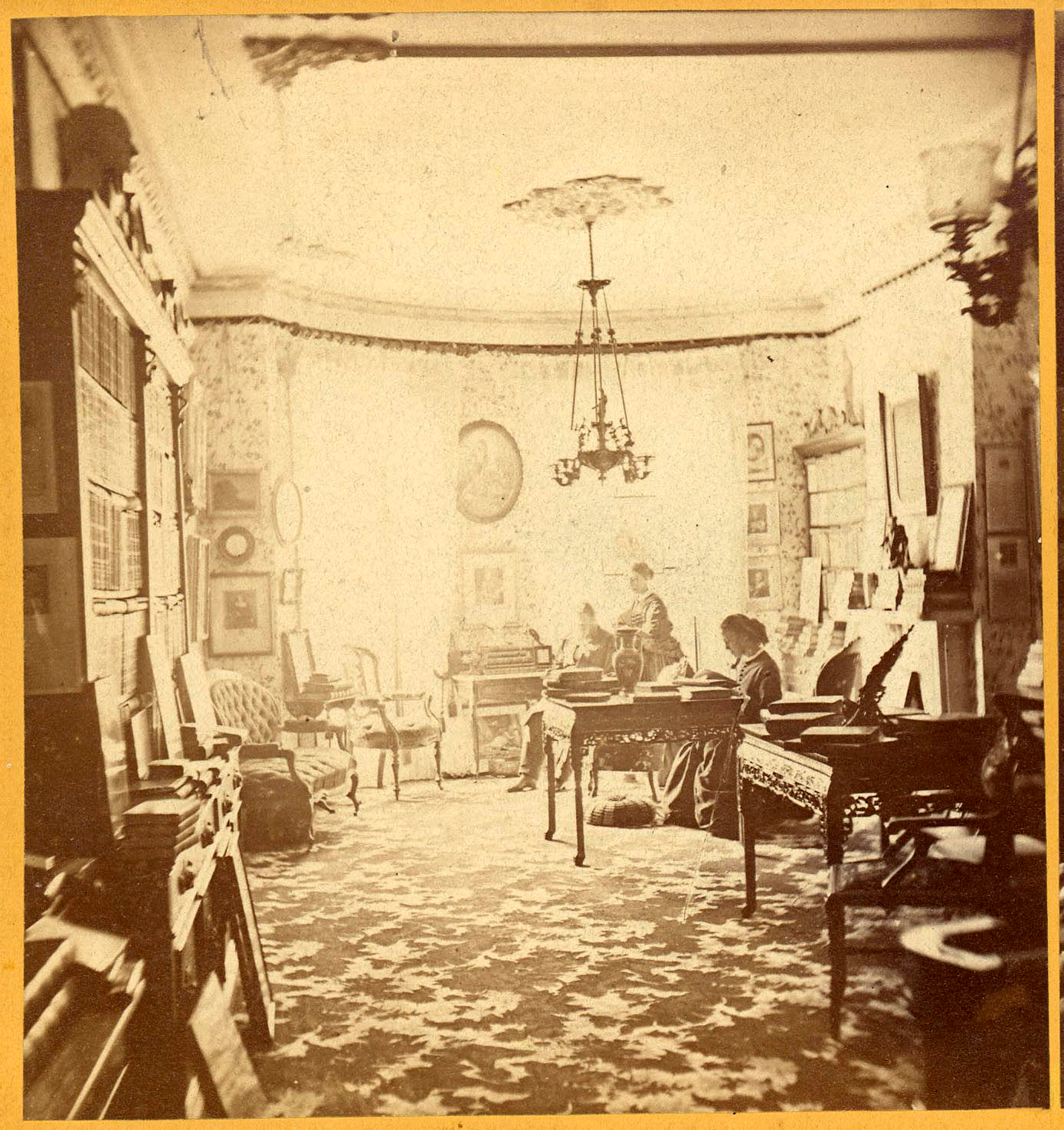

Front reception room at 71 Chester Square, home of Rev. Robert Cassie Waterston

and his wife, Anna Cabot Lowell Quincy - Stereoview, circa 1875.

(private collection)

The back of the stereoview bears a handwritten inscription:

"Chester Sq., Boston, Mass - Parlor. -

Rev. + Mrs R.C. Waterston in

the background.

Miss Mary Quincy sitting at

the table"

Peter Greene Munro (1808-1882) lived at No. 55 with his wife, Sarah Mumford Willis; his daughters, Susan and Martha; and three servants. Descending from a prosperous mercantile family, Peter had always expressed great interest in politics, but his mild nature did not consent him to be an assertive figure in the city’s complex political life. Still, his financial independence permitted him to enjoy a life at the service of the community’s welfare while being in contact with many of its political and cultural leaders through his vocation as a Justice of the Peace.

In 1868, a few years after the Munros moved from their house in Jamaica Plain to Chester Square, Peter’s oldest daughter, Maria Louisa, returned to the household, this time with her six-year-old son, William Munro. Her husband, William Henry Seavey, had been the principal of the Girls’ High and Normal School in Boston, an experimental institution founded by the educator and pioneer in women’s education George Barrell Emerson (1797-1881) and modeled after the English High School for boys, which Emerson had himself led as the first headmaster. Sadly, William Henry died at age forty-five, after an illness that had marked most of his adult life. A few years later, the young William Munro developed an interest akin to that of his grandfather, but his career in Boston’s political life was only at its early stages when death prematurely claimed him, at age forty, in 1902 – tragically, of the same disease that had affected his father.

Following the death of Sarah in 1875 and that of Peter in 1882, Maria Louisa remained in the house with her sister Martha until 1899, when they moved to Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. According to a long-held tradition, as the youngest daughter, Martha had remained unmarried to attend to the necessities of her ageing parents. In 1935 she was still the owner of an ocean-front summer home in Mattapoisett, just southwest of Cape Cod, where her father had left the world more than fifty years earlier.

The ship merchant Nathan Crowell lived two doors away from the Munros, at No. 51, with his wife, Adeline Howes; their six children, Adeline, Ellen, George, William, Elizabeth, and Charles; and three servants. They had moved there in the mid 1850s, and occupied one of the first homes to be built on the square, at one of the most desirable locations – facing the central fountain, on the eastern side. The 1880 census shows that Nathan’s three daughters were no longer living with their parents, while his three sons, all in their twenties, were still living at home.

Oil portrait of Nathan Crowell, ca. 1855

Adeline died in 1888, and by the end of the century Nathan had turned No. 51 into a lodging house. The large dwelling was shared by his bachelor son, William, and ten tenants, among whom a capitalist and his wife, three waitresses, two school teachers, and a woman composer and music teacher. Despite his active partnership in the mercantile business, Nathan preferred a quiet existence, and remained at his residence on the square for nearly five decades until he passed away, in 1904, at the age of eighty-six.

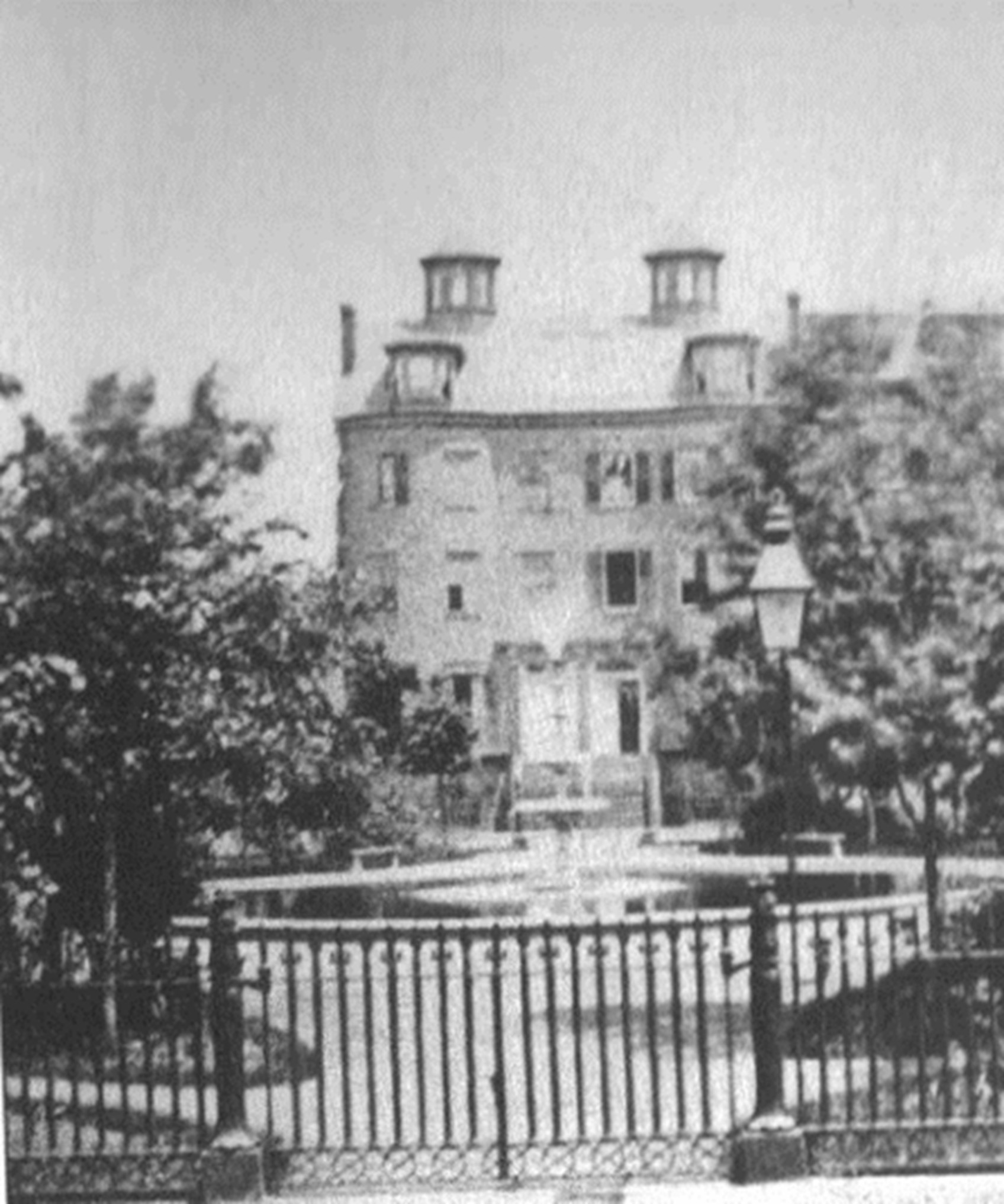

No. 51 had a twin entrance to that of No. 53, the residence of Frederick Howes (1812-1882), also in the mercantile industry. The household included Frederick and his wife, Eliza Meriam; their three daughters, Lucy, Mary, and Coraline; and two servants. The two homes at Nos. 51 and 53, built ca. 1852-53 as a two-family dwelling with a common stoop and decorative cupolas that served as stairwell skylights, were an imposing presence in the middle of the square. They mirrored the two buildings across the garden, at Nos. 54 and 56, and provided exclusive views of the fountain and the fish pond.

Nos. 53 and 51, homes of Frederick Howes and Nathan Crowell,

seen from the southern side of the of the square, ca. 1865

The home of another ship merchant, Osborn Howes, was at No. 67 – a desirable address, as it occupied one of the lots on the curved end of the square, which afforded a more architecturally distinguished façade. Born in 1806, at age sixty Osborn moved to No. 67 with eight of his nine children, shortly after the death of his second wife, Abigail Crowell (1814-1865). His first wife, Hannah, Abigail’s sister, had died in 1835 at age twenty-four, giving birth to their firstborn while the couple was living in the nearby Dorchester. Given the size of the household, which included four servants, the home at No. 67 was ideal because its larger floor plan afforded more living space than that of most buildings surrounding Chester Square.

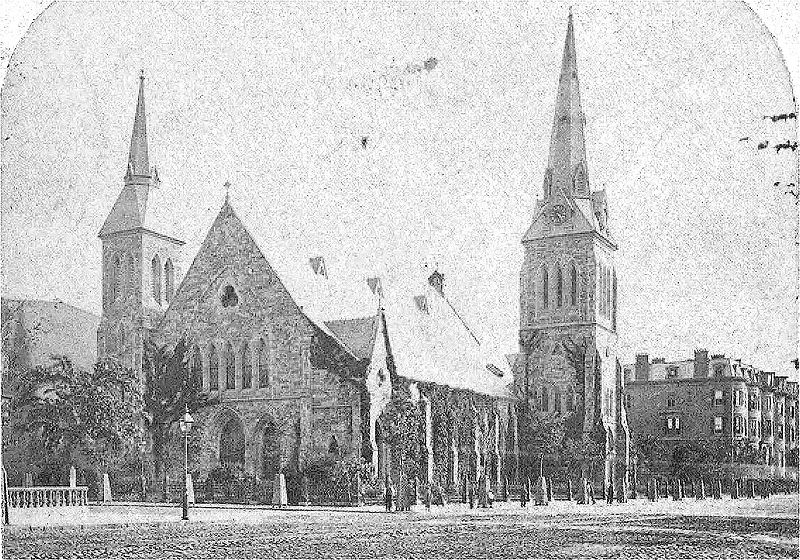

In 1867, Osborn married a third time. His new wife, Alma, a widower, was thirteen years his junior. But as his children reached adulthood and left the home, No. 67 became filled with solitude. Only his youngest, unmarried daughter, Edith, remained. Osborn insisted to retain three servants on the staff, even though the household had shrunk from thirteen to three. He still lived with three maids a decade after Alma passed away in 1882, at the age of sixty-two. The silence in the large home was broken only by the regular strokes of the bell from the nearby Methodist Episcopal Church on Tremont Street, one short block from the back of No. 67, facing West Springfield Street.

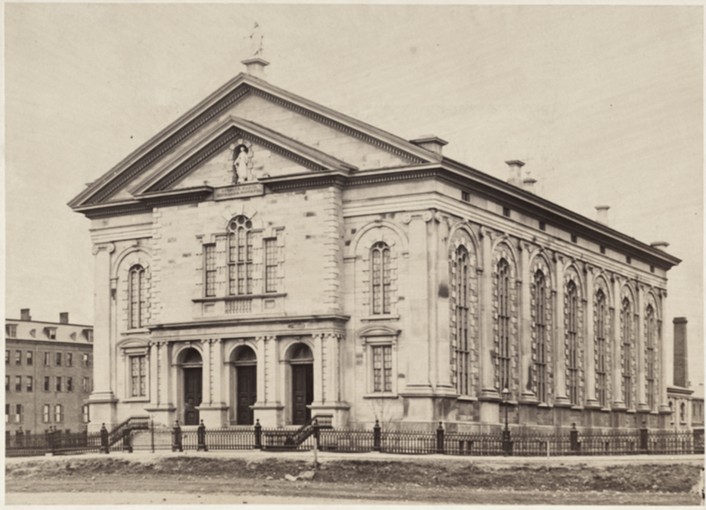

Stereoview of the Tremont Street Methodist Episcopal Church, built in 1862 from a design by architect Hammatt Billings

(private collection)

The lively and friendly voices of the three maids accompanied Osborn’s last moments, when he passed away at the house in 1893, assisted by Edith, who had lived next to him all her life.

Photograph of Osborn Howes, ca. 1880

The Howes and Crowell families who lived at Chester Square were related not only through the partnership of Nathan Crowell, Osborn Howes, and Frederick Howes in their successful firm, Howes & Crowell: Osborn’s first and second wives, Hannah and Abigail, were Nathan’s older sisters; and Nathan’s wife, Adeline and Frederick were Osborn’s first cousins.

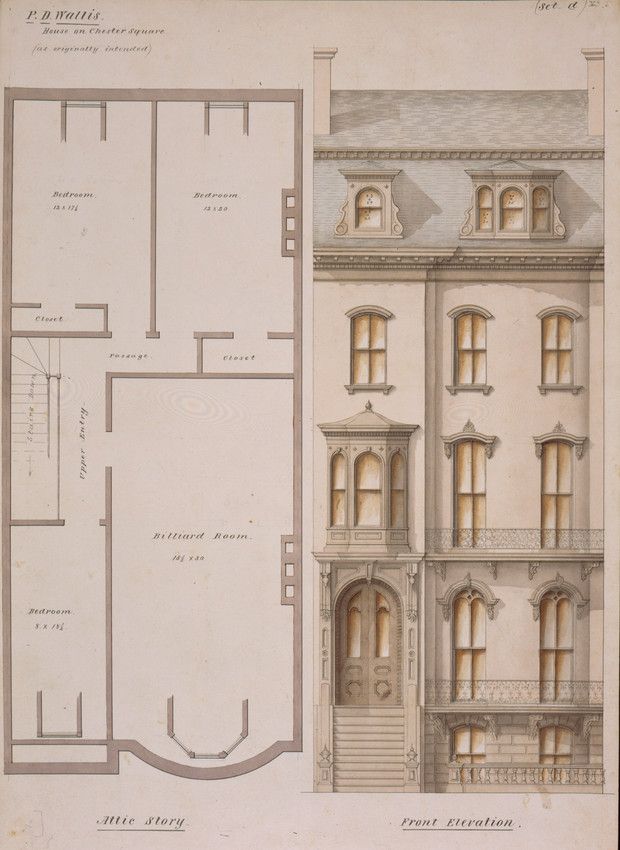

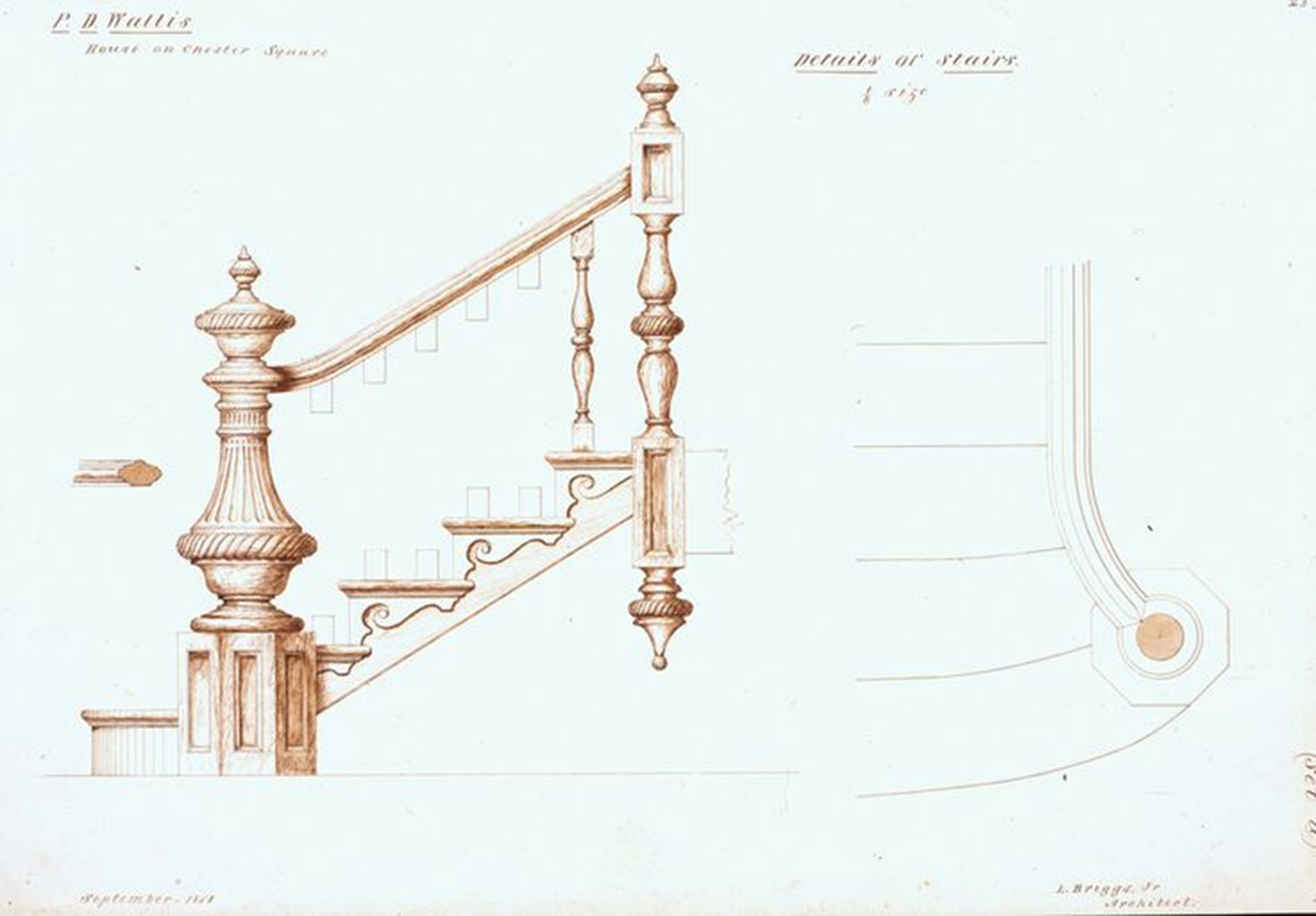

Next door from Osborn Howes’s address, at No. 65 stood one of two homes built by Paul Dean Wallis, a builder and land owner who pioneered much of the real-estate development of the Back Bay during the 1860s. Wallis purchased the lots for No. 63 and No. 65 from the city of Boston in 1858 for about $5,900, and commissioned architect Luther Briggs Jr. (1822-1905) to design elaborate facades and interiors. Several of Briggs’s original ink and wash drawings for the façade, floor plan for the attic, and design for the baluster of the first-floor landing of No. 65, have survived.

Luther Briggs Jr.: Ink and wash drawings for the façade, and for the floor plan of the attic of 65 Chester Square

(Historic New England collection)

Luther Briggs Jr.: Ink and wash drawing for the design of the baluster of the first-floor landing of 65 Chester Square

(Historic New England collection)

Both buildings boasted octagonal stairwell skylights, similar to the ones already on display at 51 and 53 Chester Square - an element that was originally missing when the initial drawings shown above were prepared.

In March 1860, No. 65 was purchased by Francis Dane (1818-1875), a successful shoe and boot manufacturer, for the exorbitant sum of $20,500. The architectural details in Rococo Revival style were exquisite. No. 65 stood out among its neighboring buildings because it sat at the beginning of a curved ending of the square, affording additional depth and a uniquely shaped façade.

Dane soon moved to Chester Square with his wife, Zerviah Brown, along with two servants. Originally from Hamilton, Massachusetts, Dane had lived in South Danvers, Massachusetts for many years - since he had opened his own business in Danvers as a youth. Having his shoes and boots manufacturing business greatly expanded while in his thirties, in 1857 he moved the offices of Dane, Wheeler & Co. to 45 Kilby Street in Boston. Living at Chester Square relieved him from long commutes, and allowed him to interact more easily with the city's upper middle class.

The Danes had no children, and enjoyed entertaining at their new home. In addition to his business, listed after 1859 as Francis Dane & Co., Francis had major investments in real estate and financial trading. He died unexpectedly in 1875, at his summer home in Hamilton, Massachusetts - of an attack of apoplexy, as several Boston newspapers reported. Zervia continued to reside at 65 Chester Square after Francis's death, outliving him by two decades.

Today 65 Chester Square hosts the headquarters of the South End Historical Society, an association whose goal is to preserve the architectural integrity and historical legacy of the neighborhood. Most of its interiors have been preserved in their nineteenth-century appearance.

65 Chester Square in the summer of 2012

Right across the park, on another curved end, stood a block of five distinguished houses. Designed in 1856-57 by John Rouestone Hall, they were completed in early 1859 by using the finest materials. Their addresses were 68-74 Chester Square, and their striking, imposing architectural elements immediately caught the eye as one walked or drove along the north-eastern curve of the park and looked to the left.

No. 70 was the home of William Cumston, partner at the piano manufacturing company Hallett & Cumston. Cumston purchased the newly built brownstone in 1859, and lived there with his wife, Jennette McArther Schouler; their three children, Mary, James, and Elisa; and three servants. Born in Saco, Maine, in 1813, William moved to Boston in his early twenties. Shortly thereafter, in 1838, he established a partnership with piano makers George Lord and Lemuel Gilbert. A year later, the firm was renamed Lord & Cumston when Gilbert left to join a different company. It was not uncommon for piano makers of the mid nineteenth century to join new ventures, and Cumston found himself involved in many such enterprises. After a few years in partnership with George Lord, Cumston decided to expand his business by joining one of the most prestigious companies in Boston – Brown & Hallett. Originally established in 1835, the firm was joined by George Davis after Brown’s retirement in 1843. Davis retired four years later, and Cumston joined forces as part of the Hallett, Cumston & Allen firm. Allen left in 1850 to form the Brown & Allen Piano Company, and Hallett and William Cumston joined in partnership.

The popular Hallett & Cumston factory and showroom were located downtown, at 339 Washington Street – a convenient fifteen-minute carriage ride from the square.

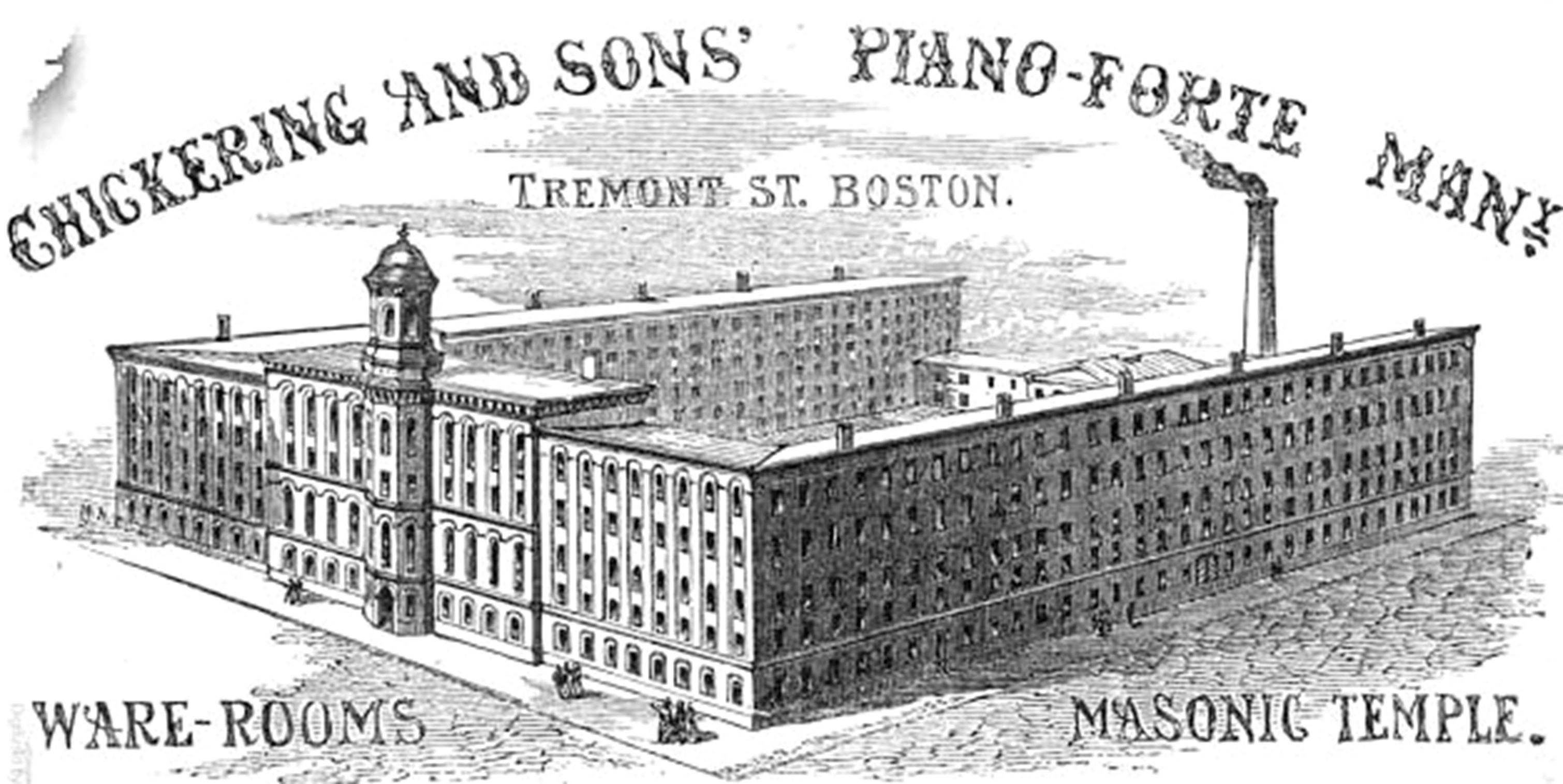

A rare 1853 full-page advertisement for the piano firm Hallett & Cumston

(private collection)

In the 1850s, Cumston patented a device (US no. 1275), to be implemented on grand pianos, which allowed two of the three strings to be completely muted by virtue of depressing a pedal that inserted a wedge between them. The effect was that of the una corda pedal on early French and English instruments. Nothing came out of it.

In May 1862, at the height of the Civil War, not yet twenty years old, William’s son James (1842-1913) enlisted in the Massachusetts 4th Infantry Battalion. Honored with the grade of second lieutenant, he returned to Boston thirteen months later. James soon became a junior partner at Hallett & Cumston. In 1867, he married Charlotte Greene, daughter of famed journalist Charles Gordon Greene (1804-1886). Her family’s home was at 163 West Springfield Street, just around the corner from the square, one short block from Cumston's residence. After William’s premature death in 1870, at age fifty-six, James assumed senior partnership at the firm until its dissolution in the mid 1890s. Over the decades, the company changed its name several times. In 1879 the name “Cumston” was removed, when the company was incorporated as part of the Hallett, Davis & Co.

James’s sister, Mary, married successful Boston banker Spencer Welles Richardson (1834-1914), whom James had met on the battlefield. Both James and Spencer returned to Boston in June 1863. James introduced his friend to Mary shortly after, and the two were married a year later.

James Schouler Cumston, left; and Spencer Welles Richardson, center – on the field, ca. 1863

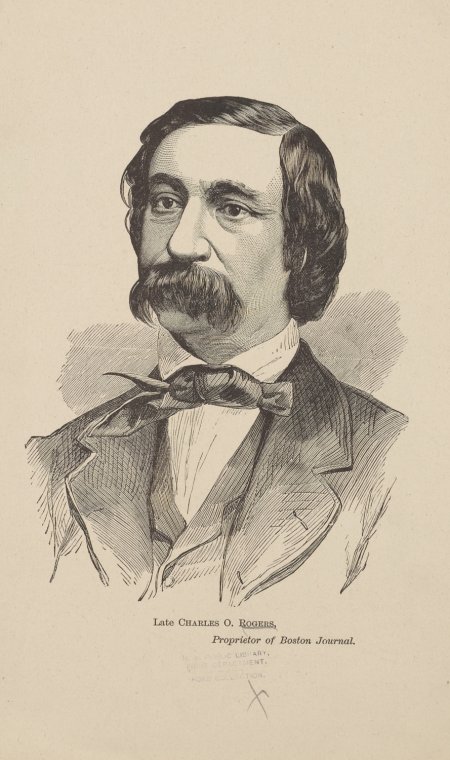

72 Chester Square, also part of the block of distinguished homes designed by John Rouestone Hall, was the residence of Charles Owen Rogers (1818-1869), the owner of the Boston Journal. Rogers lived there with his wife, Louisa Willis Coe; his four childen, Charles, Louisa, Thomas, and Mary; and three servants.

A portrait of Charles Owen Rogers, 1868

Born in Worcester, Massachusetts, Rogers became involved in the world of publishing when, as a youth, he began to work with his father and brother. Upon their deaths, in 1855 he became the sole proprietor of the newspaper. Involved in politics, he was one of the delegates to the Chicago Convention, which elected Abraham Lincoln. Despite his role as the leader of the Boston Journal, in 1861 he enrolled in the 2nd Battalion of Infantry, and was elected captain that same day. For years, after his return from the field, people called him "Major." At the time of his sudden death, at age fifty-one, Rogers had amassed a huge fortune, calculated at $1.5 million.

72 Chester Square in the winter of 2011

A rare article, published in 1859 by the Boston Saturday Evening Gazette, describes Charles Owen Rogers's home in detail. It is worth reporting it in its entirety:

"Chester Square was laid out and sold at public auction by the city of Boston, October 30, 1850, the city guaranteeing to build fences, lay out walks, and plant some shrubbery and forest trees as would make the same ornamental, previous to 1852. Very little building was done for the first few years, some two or three houses only, but during the last four years the improvements have gone on rapidly, so much so that out of the original forty lots fronting on the square, there are but three or four left vacant, and these are held by those who will soon commence building; and to show still further how the square has improved, lots that sold 8 years ago for eighty-five cents per foot, are now sold for three dollars per foot. The fifty lots not facing the square, but the mall leading from Washington Street, have fine houses erected upon them, and are nearly all occupied. Among the many improvements here, there are none more striking and pleasing to the eye than the new block designed by John R. Hall, architect, and built under his personal supervision, situated on the left hand of the square passing from Washington Street. The houses are four stories high. The house immediately in the bend, and commanding an entire view of the square, was built to order for Charles O. Rogers, Esquire, under his daily inspection. The basement story contains a large dining room sixteen by twenty-two feet, with circular ends, and two closets attached; in the rear is the wash-room, fitted up with soapstone, etc., in the best manner; and connected with this in the ell building is a beautiful kitchen fifteen by twenty-two feet, with all the conveniences that can be put into the same. The woodwork of this story is of chestnut, and finished with an extra surface. The parlor story is reached by ascending eleven stone steps, into a vestibule three by ten feet, finished with an Italian marble floor and plinth. The drawing room is sixteen by forty-two feet, and thirteen feet high, with circular ends. Adjoining this room is the parlor, oval in form, size fifteen by twenty-two feet, the passage connecting these rooms has nitches (sic) on each side, and the communication is cut off by a sliding window, which conforms with the others. These rooms are finished richly, but not gaudily. The cornice is full Corinthian, the doors are of a new pattern, designed by the architect expressly for Mr. Rogers, and of solid black walnut with silver mountings. The doors in the oval room are made to conform to the circle; this story contains four closets and hot and cold water and iron safe. The front staircase is built of black walnut, and continues from basement to billiard room in attic story, with one continuous rail. The post, rail and balusters are of a new pattern, designed expressly for this house, and finished with rope mouldings and rosettes; the black walnut is all filled and finished with an extra dead polish. The chamber story contains four rooms; the two principal chambers are sixteen by eighteen feet, with large closets and waterworks connected. The bathing room connects with the family chamber, and is finished in walnut with all latest improvements. The chamber over parlor is fifteen by sixteen feet, and the ladies’ boudoir over the vestibule and hall is eight by fourteen feet, with bay window facing the square and looking down towards Washington Street; this room is finished in green and gold, and commands one of the finest views in the square. The second chamber story is similar to the first, and supplied with all the conveniences. The upper story contains a billiard room and three sleeping apartments. The house contains eighteen rooms and about thirty closets. The exterior is built of facebrick and freestone; the basement is laid off in rustics, with panel faces; the buttresses to entrance are of scroll pattern; the doorway is circular headed with double, three-quarter columns, with carved caps in recess to door; the cap over the door is supported by double carved tresses, and above this is a perforated stone balcony; the window caps are of stone; pediment heads supported by carved tresses. The cornice is of wood, with carved truss, double dentils and guilloche in frieze, sanded in imitation of stone. The roof is French, covered with imported slate. The bay window projection, looking down the square, is of wood, ornamented with rope pilasters and carved caps, with rope over the same. The base corresponds with the balcony and the cornice with that on the house—all sanded. The front is also ornamented with an iron verandah, the pattern being entirely new; the cornice corresponding with that of the bay window. This is a new feature for houses in Boston, with bowfronts, and is decidedly taking. The house adjoining was built to order for William Cumston, Esquire, and is very much like the one already described. The block will consist of five houses; the fronts are to correspond in every particular with Mr. Rogers’s house. Two are already finished and occupied, and the other three will be ready early in the spring. Much credit is due to the architect for introducing something new and pleasing in the architectural appearance of the fronts. The work has been done in the most thorough manner, the best of materials used, and that experienced builder, Mr. Ivory Bean, has done the mason’s work for the block, which is sufficient to know that the work is well done. We understand that the two houses adjoining Mr. Cumston’s will be for sale when finished."

Detail from the front page of the Ballou’s Pictorial of July 16, 1859, showing the tree-lined mall

that led from Washington Street to Chester Square, and the surrounding homes

(private collection)

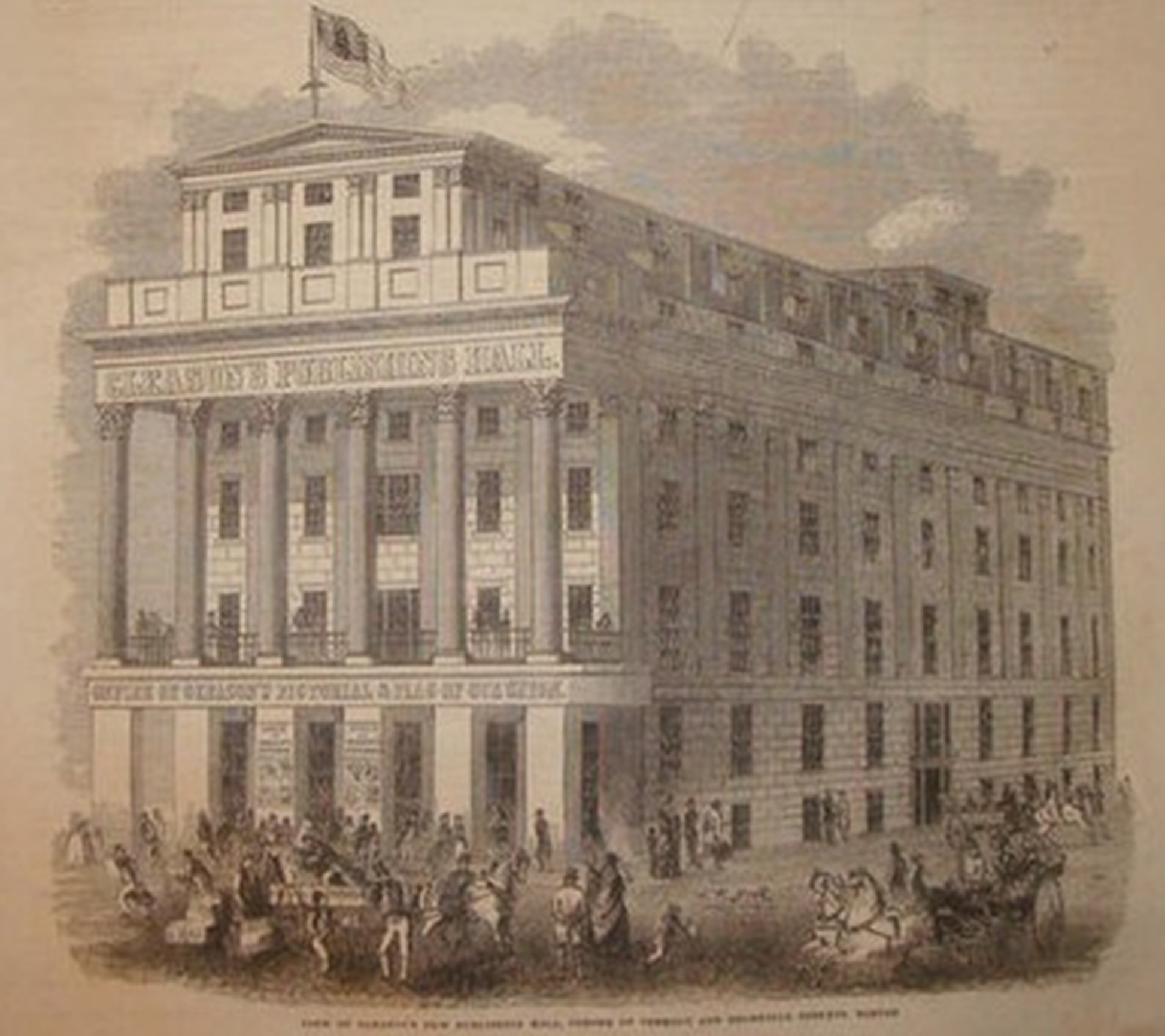

For a few years, before he moved to Marlborough Street in the Back Bay, 56 Chester Square was the residence of Frederick Gleason (1817-1896), a successful publisher whom the Boston Globe described as “the father of illustrated journalism.” German by birth, Gleason moved to the United States as a youth, and worked first as a bookbinder, then in the 1840s as the publisher of the one-hundred-page paper-covered story books that became America’s first “dime novels.” In 1851, upon returning from extensive travels in Europe, he created the Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion (later renamed Ballou’s Pictorial), a weekly periodical modeled after the Illustrated London News. It featured the work of artists such as Winslow Homer and William Waud, and its instant success brought to its founder great financial reward. His business had several locations in Boston, including the Gleason Publishing Hall at 18 Tremont Street, downtown, situated in the building that had formerly hosted the Boston Museum.

The Gleason Publishing Hall, illustrated in an 1851 issue of the Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-room Companion

(Roberto Poli, private collection)

A portrait of Frederick Gleason, from an 1852 issue of the Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-room Companion

(private collection)

Because of their prominent location on the square, facing the fountain and the fish pond, Nos. 54 and 56 were two of the first homes to have been completed, as early as the spring of 1853. Gleason had just begun to amass a conspicuous fortune through the profitable sales of the Pictorial, and securing the purchase of one of the most prominent homes at Chester Square was symbolic of his financial success. Unlike many of the bow-fronted buildings on the block, the design of Nos. 54 and 56 follows Italianate conventions, with a flat façade, a more imposing six-story structure, and large ornamental cupolas that served as skylights for the main stairwells.

54 and 56 Chester Square today – the façades

54 and 56 Chester Square today – one of the cupolas

Designed in 1857 and completed by 1859 for William Rice Carnes, a dealer in mahogany and rosewood, the building at No. 39 was probably the most extravagant property on the square, boasting lavish woodwork, elaborate plaster crown moldings and finishes, ornamental etched glass, and a billiard room on the top floor. Carnes, who had previously made Roxbury his home, lived there with his wife, Martha, his three children, and two servants. According to his descendants, at the Chester Square address Carnes sheltered fugitive slaves on their way to the Underground Railroad during the years of the Civil War, leaving the mansion in complete darkness as he pretended to be out of town for business.

A 1960s photograph of 39 Chester Square

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library

Chester Square covered in snow

photograph taken from the third-floor balcony of 39 Chester Square, ca. 1870

Courtesy of the South End Historical Society

In 1865, William's wife, Martha, died unexpectedly. William had already lost his son, William Bertram, during the Civil War, in December 1861. In 1868, Carnes sold the mansion to Nathaniel Whittemore Farwell (1818-1898), a successful cotton merchant, and removed to Holderness, New Hampshire. Farwell lived at No. 39 with his wife, Eliza; their three children, Mary Eliza, Evelyn, and Nathaniel Jr.; and three servants. After Nathaniel’s death, Eliza lived there with her unmarried daughter, Evelyn, two servants, and a nurse. She was still the official owner when she passed away at the home in 1909, at the age of eighty-nine. The building's address changed to 558 Massachusetts Avenue in 1894. After Evelyn's death in 1915, the home remained vacant until the family sold it in 1920. The new owner was the League of Women for Community Service, a group of African-American women led by Maria Louise Baldwin (1856-1922), the association’s first president. The women headed the Soldiers’ Comfort Unit at the end of the First World War, providing services to black veterans in and around Boston immediately after the conflict, as well as aiding widows in need of assistance. It was a coincidence that the home that had been the safe haven of fugitive slaves in the late 1850s and early 1860s would become the permanent headquarters of the League, and that its role in the community would still be that of providing a temporary home for those in need: during the 1940s and ’50s, in fact, the building hosted many African-American women who were studying in Boston but were not allowed to occupy the dormitories that the institutions offered to their students. Among them was a young girl, Coretta Scott (1927-2006), who studied voice and violin at New England Conservatory of Music on Huntington Avenue, a few blocks from Chester Square. In 1952, while living at the League, Coretta met the man who would become her future husband – Martin Luther King (1929-1968). At the time, King was completing his theological studies at Boston University, and was rooming at 397 Massachusetts Avenue, only two blocks away from the square. They were married the following year, at Coretta’s parents’ home in Alabama.

In the 1950s, a century after its development, the South End was a rather different place. The intersection of Massachusetts and Columbus Avenues, only steps from King’s lodging, had become one of the energetic centers of Boston’s black community, with popular restaurants, nightclubs, pool halls, and meeting places. In the evening, especially on weekends, it was not unusual to see elegant nightclub hoppers of all extractions arrive in their cars to listen to extraordinary jazz artists and some of the most famous bands of the time. Duke Ellington and Count Basie, just to name a couple, were regular guest performers at some of Boston’s most popular jazz clubs – Wally’s Paradise, the Chicken Lane, the Savoy Ballroom, Slades’, the Big M, the Wig Wam, the High Hat. Opened in 1947, of the jazz clubs at the legendary intersection, Wally’s is the only one to have survived. And as the Big Band era was fading, one of the hardest times in the history of the South End began – a period in which the area sadly bent from a social decline and much inconsiderate urbanization. In 1954, Chester Square was mercilessly cut in half by city ordinance, the motor traffic having become too heavy and inconvenient for the narrow carriage lanes curving around the garden’s perimeter. The central fountain removed, the landscaping neglected, Chester Square deteriorated further over the decades, until a recent restoration of the two halves was undertaken thanks to the efforts of a small group of residents.

Chester Square covered in snow – view from the eastern entrance, winter 2013

Because of its philanthropic designation during the following decades, No. 39 is today the only home on the square to be preserved as a single-family dwelling, with its original interiors only marginally altered from the way they appeared at the end of the nineteenth century.

39 Chester Square – the front parlor

39 Chester Square – sitting room, detail of the third–floor interior

The 1861 Boston Directory listed No. 49 as the home address of Benjamin Franklin Hallett (1797-1862), United States District Attorney for Massachusetts during the mandate of President Franklin Pierce. A prominent lawyer, abolitionist, and Democratic Party activist, Hallett was one of the first residents at Chester Square, having purchased the property in 1858. He lived there with his wife, Laura Smith Larned; his son, Henry Larned Hallett (1826-1892), also a lawyer; Henry’s wife, Cora; and two servants, Catherine and Mary. Born in Barnstable, Massachusetts, Benjamin was an 1816 graduate of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he studied law and began an active career as a journalist. He soon moved to Boston, where he was employed by the Boston Advocate and the Boston Daily Advertiser, for which he wrote with secure style and elegance. In the same period he grew interested in the ideals proposed by the Anti-Masonic Party, but their views soon became outdated. Disillusioned, though increasingly engaged in political matters, he joined the Democratic Party and ran as a candidate for Congress in 1844 and 1848. In both races, he was defeated by Robert Charles Winthrop (1809-1894), one of Boston’s leading political figures. In the 1848 race, Charles Sumner (1811-1874), another Bostonian and prominent politician, was also defeated. Sumner would make history not only for his abolitionist ideals, but especially for the brutal caning inflicted upon him by Preston Brooks during the debate on slavery at the Senate in 1856. Even though at the time Sumner and Hallett displayed differing political tendencies, the mutual interest in the cause of anti-slavery drew them close, and the two enjoyed each other’s genial company. When in Boston, Sumner was a guest at 49 Chester Square, where Benjamin and Laura frequently entertained political and cultural figures of the time in their salon.

Portrait of Benjamin Franklin Hallett, ca. 1845

(private collection)

In 1848, Hallett became the Chairman of the first Democratic National Committee, a position he held on a four-year term, and which he led with remarkable success. Consequently, in March 1853 President Franklin Pierce offered him the position of District Attorney for Massachusetts – another four-year term which made Hallett a distinguished figure in Boston’ political scene. It was at the end of the term that the Halletts moved from the smaller townhouse at 17 Louisburg Square, on Beacon Hill, to the newly built, spacious home at 49 Chester Square.

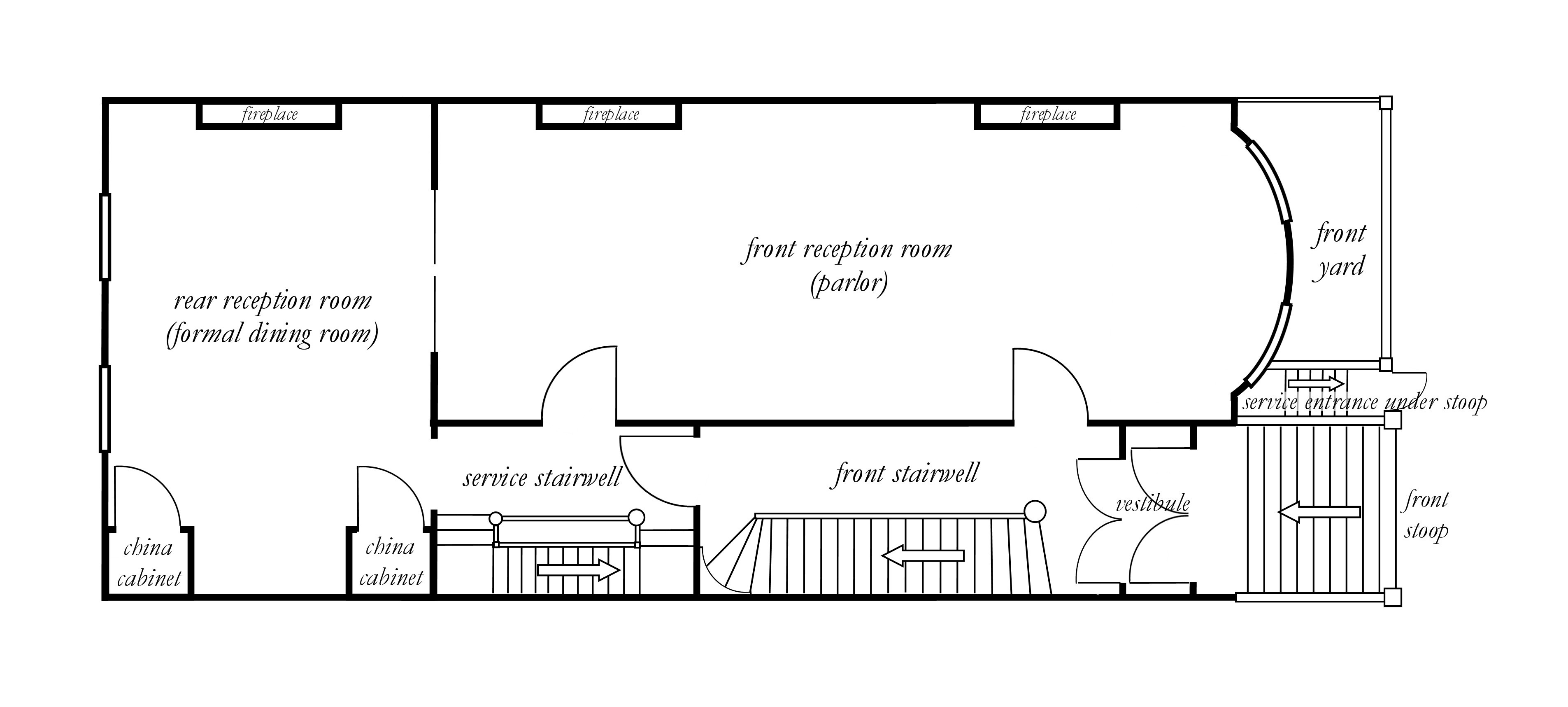

As it was typical of the houses on the square, No. 49 included a small front yard, fenced by a cast-iron balustrade whose posts were decorated with leaf motifs. With matching railings, an imposing stoop stood on the left-hand side of the yard. At the top of the stoop, two sets of elegant double doors enclosed a vestibule. It was here that visitors were ceremonially asked by the parlor maid to wait while the guest’s calling card was brought upstairs to the lady of the house. The second set of doors opened into an entryway, which featured a mahogany staircase with an attractive newel post topped by a gas-lit fixture. This was the second level, the main floor of the house, and it featured two large parlors with twelve-foot ceilings; sumptuous leaf-patterned plaster crown moldings; mahogany doors, and a set of pocket doors with decorative etched glass; three marble mantelpieces, carved with floral motifs and furnished with cast-iron decorative covers; and gas-lit brass chandeliers.

Fireplace mantel in one of the reception rooms at 49 Chester Square

The staircase from the main landing led to two floors that hosted four bedrooms and their adjoining rooms, and to the top floor with a billiard room and the servants’ quarters. At the back of the main landing was a door with decorative wheel-cut frosted glass panes, which led to an enclosed space that hosted a secondary stairwell. It was used mostly for service, but it featured elegant woodwork and plasterwork because it was frequently used by the owners as well. It connected the ground level to the reception rooms and the second-floor bedrooms. By using this stairwell, through a door-less archway on the landing of the same, the house help had access to the rear reception room, used for formal meals with guests and during holiday celebrations, bringing food and other items from the kitchen on the lower level of the building. A third door, in the middle of the landing, led to the large front parlor, which served both as the main reception area for house calls, and as an entertainment space during parties.

Floor plan of the parlor level at 49 Chester Square

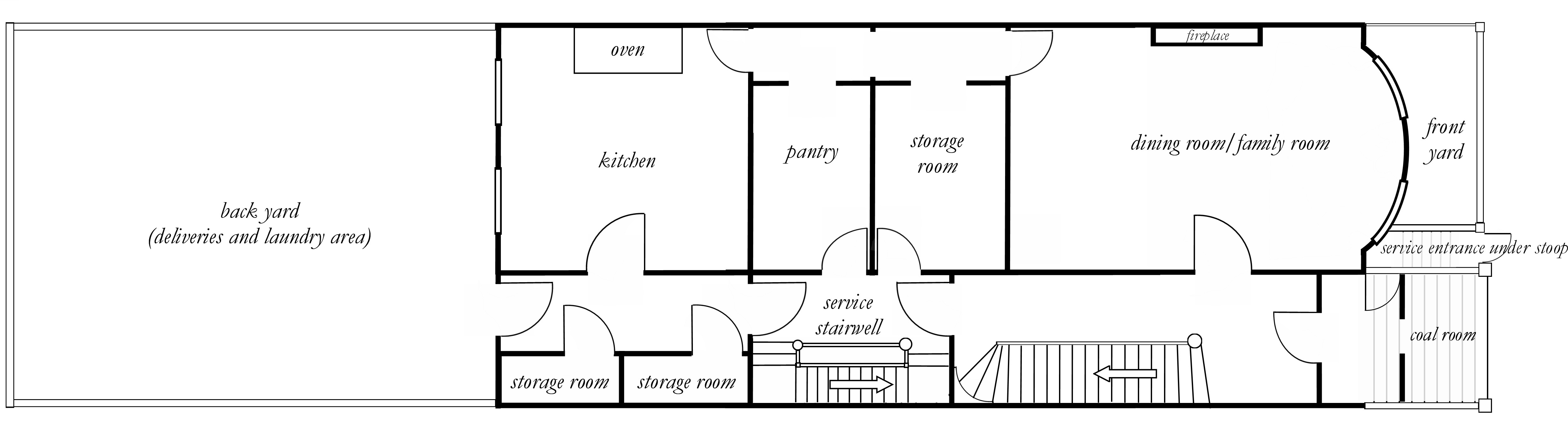

The ground floor featured a dining room, located in the front of the building; a large kitchen with built-in cabinets in the back; storage rooms; a coal room, adjacent to the service entrance under the front stoop; and a paved yard in the back of the house, which was used for the delivery of groceries and other goods, and as a laundry area. The dining room was accessed through the main staircase, from the landing on the parlor level, and was used on a daily basis for regular meals. It had two large windows, beautiful woodwork, and a mantelpiece of equal beauty to those of the bedrooms. The dining room also served as a family room: it was warm in the winter, because of its nearness to the kitchen; and the coolest room of the house in the summer, because of its location slightly below the ground level. There the family would gather in the evenings, around the light provided by oil lamps and, in the winter, by the burning logs in the fireplace as well. Various activities took place, such as reading and knitting, while conversation was carried out until bedtime was called.

Floor plan of the ground leve at 49 Chester Square

The bedrooms, though simpler in appearance than the parlor level, displayed ornate marble fireplaces with elaborate cast-iron covers, fine woodwork, and plaster crown moldings.

Cast-iron summer cover for one of the bedrooms’ fireplaces at 49 Chester Square

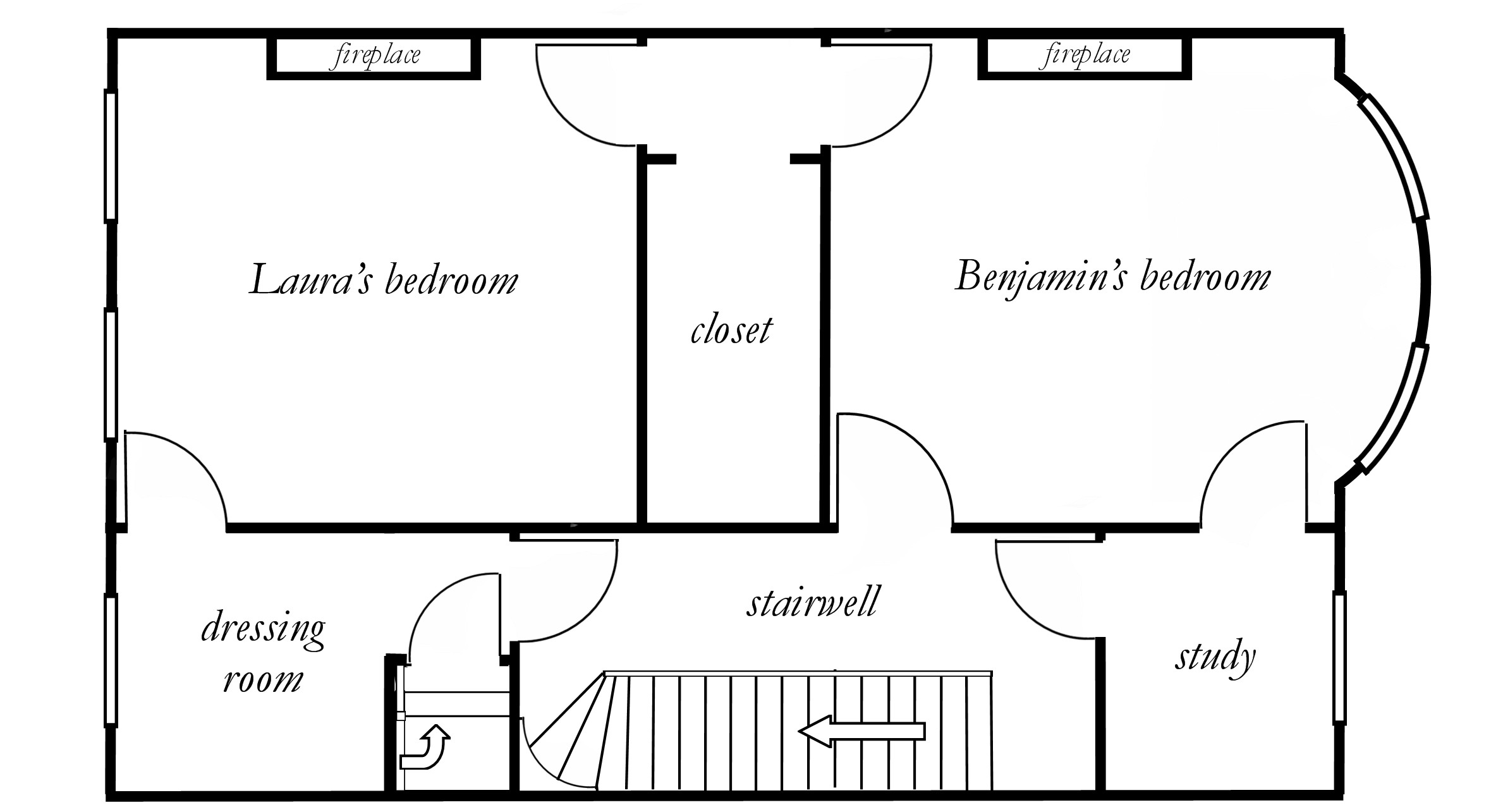

Benjamin’s private study was a comfortable small space adjacent to his bedroom, on the third-floor, right above the main entrance. It overlooked the fenced garden of the square, and had a lovely view of the fountain. The bedroom and the study were accessed via two independent entrances on the landing. Laura’s bedroom was on the same floor. It was provided with a dressing room, and faced the quiet West Springfield Street in the back. The view from her rooms included the Presbyterian Church, one of the first places of worship built in the South End in the early 1860s; and a large, empty lot that would soon be occupied by the Home for the Aged Men, a splendid building designed by the celebrated architect Gridley Fox Bryant and erected in the mid-1860s.

Left: Presbyterian Church at West Springfield Street, built in 1860 and one of South End’s first places of worship.

Right: Home for the Aged Men, designed by Gridley Fox Bryant and erected in the mid-1860s. Bryant chose to spend his last days here.

(Ca. 1870 photographs by J.J. Hawes - Collection of the Boston Public Library)

Laura’s quarters had their own entrance through the dressing room, and also communicated with Benjamin’s bedroom through a small hallway that featured a large walk-in closet for linens and clothes.

Floor plan of the third-floor, including the two main bedrooms and adjoining rooms

It was in her bedroom that Laura unexpectedly died of bilious fever in early May of 1860, sixty-two years of age – a tragic event that prevented Benjamin from attending the Democratic Convention in Charleston, South Carolina, for which he had been chosen as a delegate. But life and death alternated seamlessly even in the happiest and wealthiest homes. Another episode, this time joyous, kept Benjamin from traveling south: only a few days later, in the upper rooms at No. 49, Cora gave birth to a daughter whose name, Laura, was chosen to commemorate the grandmother who had just passed away. It took a few weeks for Benjamin to return to his work. He tried to regain the seat as a delegate at the Baltimore convention two months later, but he was denied the privilege. Defeated, he returned to Boston, where he spent the remaining two years of his life in the practice of law. His failure to attend the Charleston convention had not been the sole cause of Benjamin’s decline: there was more to the story.

Almost a decade earlier, in September 1850, the Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Law, a bill that enforced the return of fugitive slaves to their masters, and that threw the entire justice system into a state of chaos. Indeed, many of the figures who were involved in both the institution of the law and the political life of the country felt powerless in front of what The New York Evening Post described as “an Act for the Encouragement of Kidnapping.” Benjamin Franklin Hallett, both a radical abolitionist and a man of law, was between two fires: while on the one hand he served the law, on the other he was forced to stand against the rights of the people, which he had supported vehemently in his early work as a journalist and active anti-slavery proponent. His position as a United States District Attorney forced him to use “reasonable force or restraint as may be necessary under the circumstances of the case” (Fugitive Slave Law, 1850; Section 6) to return fugitives to the claimants.

In 1854, as the Halletts still lived at Louisburg Square, the most famous case in America’s slavery history put Benjamin on his knees. Anthony Burns (1834-1862), who had escaped from the estate of Charles F. Suttle in Alexandria, Virginia, found refuge in Boston with the help of a sailor friend and began to work for a pie manufacturer and a clothing dealer. Discovered walking on Court Street, Burns was arrested on a warrant granted by Commissioner Edward Greeley Loring, and was brought to court. Outside the courthouse, a crowd of a few hundred people grew to about two thousand within hours. Before the trial began, a group of black men guided by white minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson plotted to rescue the prisoner. The attack was crushed. In touch via telegraph with Hallett, President Pierce requested to coordinate artillery and marines as back up to the guards who were watching Burns. About a hundred and twenty-five bodyguards began to monitor the fugitive, and hundreds of militaries were dispatched around the courthouse to ensure the safety of the people within its walls. The measure, viewed as unlawful and humanly cruel, drew national attention causing public demonstrations, protests, and an attack on United States Marshals who were guarding the courthouse. A group of abolitionists managed to raise $1,200 to free Burns – the sum Suttle had requested as a payment for the slave’s return. But as the action was considered unauthorized and illegal, Hallett was forced to prevent the arrangement from being carried out. Benjamin’s son, Henry, had been appointed Unites States Assistant Attorney in 1853, and worked closely with his father. That day, Benjamin and Henry were attacked on the street, during their short walk back home from the State House: “a gang of negroes, […] were about to commit violence upon their persons, when an alarm was given. The police rallying, the black rascals fled,” the Rossville Weekly Sentinel in Rossville, Ohio reported on June 6, 1854. Even though Burns was represented by one of the most prominent Boston attorneys, the Fugitive Slave Law spoke clearly: the trial was considered a mere formality, and Commissioner Loring sent Burns back to Virginia. Almost fifty thousand people watched him as he left the courthouse. Stores were draped in black in solidarity; as he was escorted through the streets of Boston, people exploded in vehement protest, spitting on the militaries and screaming "shame! shame!" A few weeks later, Suttle sold Burns to David McDaniel, a cotton planter from North Carolina. With the help of a group of northern abolitionists who had closely followed the trial and opposed its outcome, Burns was ransomed from McDaniel for $1,300. He returned to Boston as a free man, eventually receiving an education in theology at Oberlin College in Ohio thanks to a scholarship. Shortly after graduating, Burns moved to Southern Ontario, where he became a Baptist preacher and served as a non-ordained minister until several years later, when he died from tuberculosis at the young age of twenty-eight.

What remained of the episode, witnessed by thousands of people, was a Hallett portrayed as a coward and a political machine, a man who was acting in the interest of his career. But there was of course a more nuanced side to the event: as Paul Finkelman pointed out in the introduction to his study Bondage, Freedom & the Constitution, a case study of Burns’s trial, “judges and lawyers seek to enforce and uphold the law while also proclaiming an interest in an abstraction we call justice. As we know, there is often a tension between the two. Consequently, serving the law often means not serving justice.” Hallett’s decline in popularity, caused by his role in Burns’s trial, may have been responsible for his eventual political failures – unjustly, as he vehemently supported abolitionism and the activity of the Underground Railroad, in which he might have been involved. The unsuccessful attempt to regain his seat as delegate at the Baltimore Convention was one last disappointment.

Benjamin’s sudden death in September 1862 prompted Henry and Cora, who was expecting their second daughter, Constance, to leave No. 49 and move to 31 Chester Square. What caused this decision, given that the two homes were of equal size and only fifty yards apart, is not known. Was it their reluctance to occupy the two bedrooms that had been of Benjamin and Laura, in which they had passed away?

Henry Larned Hallett lived at No. 31 until 1888, when he moved with Cora to the Back Bay. His sister, Jane, had married Francis Willard Sayles, a wealthy Boston merchant, and inherited an enormous fortune when he died in a tragic train accident in Connecticut. He was twenty-nine years old. By the early 1870s, Jane was living with her daughter, Laura, at an exclusive address in the Back Bay (42 Commonwealth Avenue), whose construction she had commissioned in 1868. Henry died in December 1892, only months before Chester Square's addresses were renumbered by the city of Boston as Massachusetts Avenue.

At No. 29, next door from Henry Hallett’s new address, was the residence of Elizabeth Sumner Harraden. Eliza, as she was called, moved to Chester Square in 1862 with her daughter, Anna; her son in law, John Henry Willcox (1827-1875); and two servants, Lucy and Bridget. Born in Savannah, Georgia, Willcox was a well-known musician, and covered the position of organist and choir master at the nearby Church of the Immaculate Conception, on Harrison Avenue, adjacent to the early settlements of Boston College. Willcox joined William Benjamin Dearborn Simmons as a partner of his organ building firm in 1858.

Church of the Immaculate Conception on Harrison Avenue, built in 1861, photographed ca. 1865

(private collection)

Church of the Immaculate Conception, interior - photograph, ca. 1875

(private collection)

Eliza was well-known in the neighborhood, as she was the widow of Jonas Chickering, the founder of the Chickering Piano Manufacturing firm. They had married in Boston in November 1823. Jonas was born in 1798 in the small village of Mason, New Hampshire. At the age of twenty he moved to Boston, where he worked for cabinet maker James Baker. He had already gained considerable experience during the three years spent as an apprentice in the workshop of another cabinet maker, John Gould, in the town of New Ipswich, near his birthplace. A year later he was working for John Osborn, who owned a small piano-making business. In 1823, Jonas decided to form his own company, and established a close partnership with James Stewart, a Boston piano maker. That year, their first efforts produced fifteen pianos, the first one of which sold for $275. The relationship with Stewart did not last, however, and by 1827 Jonas was working independently. In 1830 another partnership was secured, this time with John McKay – a productive collaboration, at first under the name of Chickering & Company, then Chickering & MacKays, which lasted until MacKay’s untimely death in 1841. Two decades after its inception, the company already enjoyed great success thanks to its owner’s dedication, genius, and audacity, and on account of his humility and camaraderie: not only did Jonas address the building of pianos with utmost devotion, displaying great interest in acoustical and technological improvements; he also showed appreciation toward his employees, whom he treated with generous wages.

In 1843, Jonas patented a one-piece cast-iron plate as a structural support for larger grand pianos, an innovation so influential that it was eventually adopted worldwide. “By revolutionizing the way pianos were made, Chickering – with the help of others – turned a modest craft operation into a major industrial enterprise,” [The Craftsman as Industrialist: Jonas Chickering and the Transformation of American Piano Making – The Business History Review, Vol. 59, no. 3, Autumn, 1985] said Gary J. Kornblith of the piano maker’s career. By the late 1840s Chickering was one of the leading manufacturers in the United States, and his work was recognized at an international level when he was honored with a gold medal at the 1851 London World’s Fair. Such was his impact in the world of piano making that in 1852, of the nine thousand pianos produced in the country, one thousand were made by the Chickering firm. By the mid 1850s, Chickering was manufacturing about 1,500 instruments per year, a production whose revenue amounted to $200,000.

Portrait of Jonas Chickering, ca. 1850

from "Popular Science Monthly," Volume 40 (1891-1892)

The company’s headquarters was originally located at 334 Washington Street, on the same block as William Cumston’s factory. It was a five-story building that Chickering had built with MacKay in 1837, and which hosted a large wareroom and a small performance hall. The factory was located near Boston’s major artistic neighborhood, and became a sanctuary for musicians who toured from other parts of the country and from abroad, and for those who paid homage to the musical art by attending their performances.

After fifteen years of growing popularity at Washington Street, however, the future of Chickering’s business was marred by tragedy: on the night of December 1, 1852, the building burned to the ground in a terrible blaze. Much loss was experienced, including the tragic death of a watchman.

An 1854 lithograph depicting the fire at the Chickering Factory

(private collection)

The damage was estimated at about $250,000, half of which was uninsured. The New York Times reported:

At about 11 o’clock last night a fire broke out in the case-room of the third story of the extensive Piano forte establishment of Jonas Chickering, No. 334 Washington-street. The flames spread with great rapidity, and in a short time the upper part of the back building was in flames. […] The building […] was fitted with every convenience for his business, without regard to expense. […] there were in the building at the time 100 pianos finished and unfinished […] there were also a large number of patterns and moulds, which were very valuable, and can with difficulty be replaced. About one hundred persons were employed in the building who have all lost their tools, and some of them money and clothing. […] at the height of the fire the walls of the burning building fell in different places […]. A portion of the side wall on Sweetzer’s Court first fell, but did no injury; but when the gable end of the wall on Norfolk Place fell and destroyed the Blake building, it also buried in the ruin two watchmen who were in the building – one name A. M. Turner of the Centre Division, and the other was Benjamin F. Foster of the Boylston Division. A large force set to work to clear out the ruins, in order to rescue the men, if possible. After proceeding in the work for some time, the voice of Turner could be heard, and at length one of his arms was reached; but just as they were about the extricate him, he fell into the cellar. At length, after nearly three hours, Mr. Turner was taken from the ruins in a living state. {…] the body of Mr. Foster had not been reached at 11 o’clock, though men were steadily at work on the ruins. It is supposed that he was instantly killed. He was employed at the establishment of Hallett and Davis. […] the heat of the fire was so intense that the buildings on the opposite side of the street were several times on fire, and were with difficulty saved. […] in relation to the origin of the fire, we learn that an hour before the fire broke out, Mr. Clapp, the foreman of Chickering’s establishment, passed through the entire building with a lantern, and ascertained that all was right. He had returned to his house, which adjoins the establishment, and was just about going to bed when he saw the light of the fire, and immediately gave the alarm. […] the fire occupied the Department uninterruptedly for five hours.

The Boston Atlas reported in a mournful tone that

It is not a mere Piano-Forte Factory which has been destroyed, but a familiar temple of music, to which not only our own worshippers have paid daily devotion, but into which the pilgrims from many a foreign land have come […]. Mr. Chickering’s loss is not to be measured by money. The patterns, the scales, and all the drawings, which have been the results of his long experience and close calculations, the work of many an evening hour of patient thought, have all been destroyed in a night. One instrument in particular will be a great loss. For a year past Mr. Chickering has been engaged in planning and constructing a new piano, which would possess many advantages over those now used in parlors. He had spent weeks and weeks upon its preparation, and had got it so far completed that in a day or two it would have been ready for exhibition. This instrument, with all its patterns and scales, is destroyed with the rest.

But Chickering did not let the catastrophe impede his trade: plans were quickly made to use some land adjacent to the ruins, though a large vacant lot just half a block from Chester Square, on Tremont Street, was eventually favored. With no time to waste, the construction of a new factory began in the early spring of 1853.

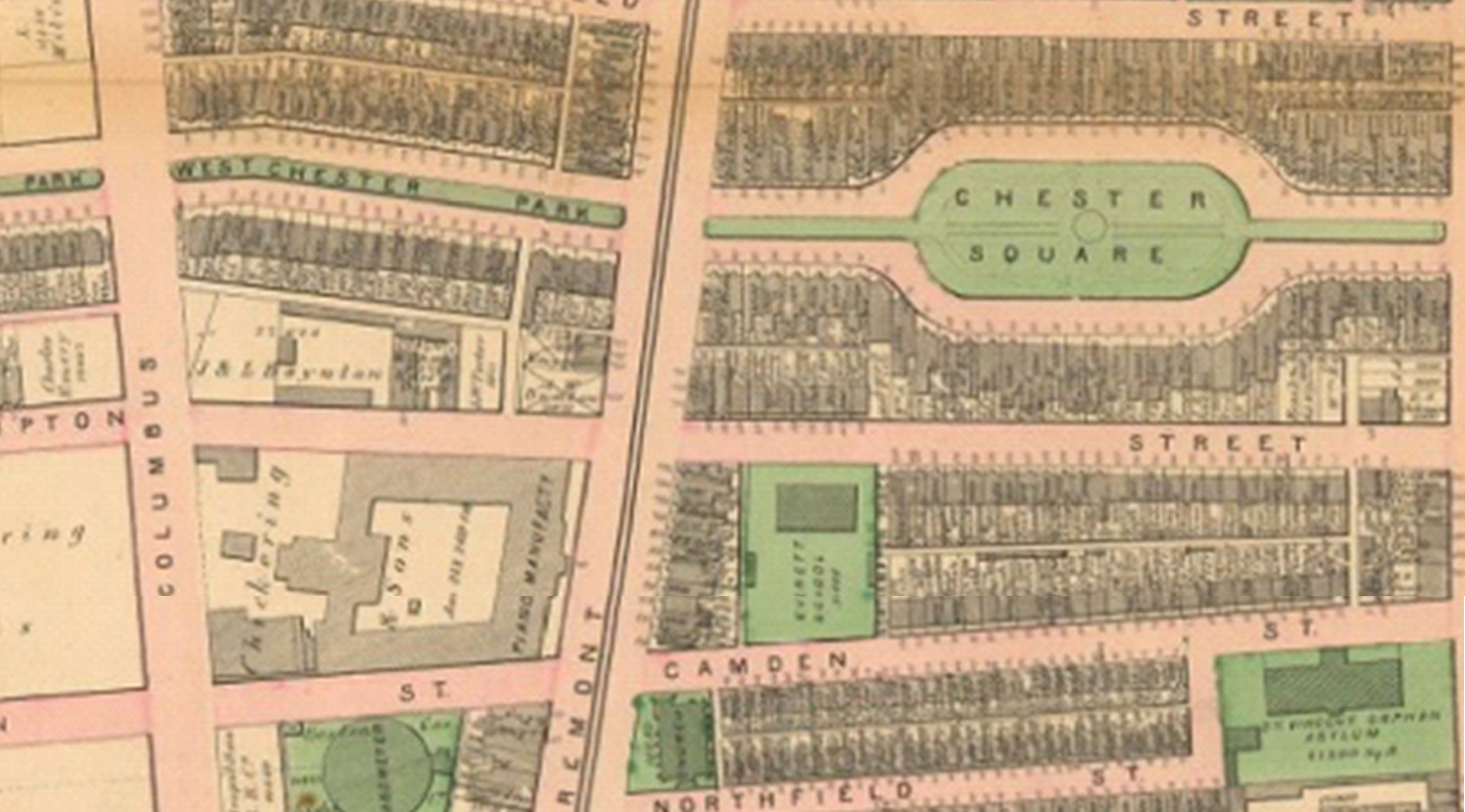

Chester Square on the right; and the Chickering Factory, outlined in grey, in the lower left

(detail of the 1874 G. M. Hopkins & Co. Map, Boston, Plate Y)

(private collection)

New energy was added to the business when, in the early months of 1853, Jonas brought into the company his three sons, Thomas Edward (1824-1871), Charles Frank (1827-1891), and George Harvey (1830-1899), and renamed the company Chickering & Sons. The four of them set out with great excitement about the new facilities, when another low blow hit the family: Jonas died of a stroke in December 1853, at the age of fifty-five, only several months away from the completion of the factory’s new location. Some eight hundred people followed the funeral procession, and the mayor of Boston, Benjamin Seaver, ordered the ringing of church bells all around the city to honor its illustrious citizen.

The firm was now in the hands of Jonas’s three sons. The most influential of them was perhaps Charles Frank, known as Frank, who inherited his father’s inventiveness and ambition: in 1867 he was to garner the Imperial Cross of the Legion of Honor, presented to him by Napoleon III for his contributions to the arts – one of over two hundred awards he received while at the helm of the company. Frank moved to New York in the late 1850s to conduct the family business there, while George and Thomas remained in Boston. George Harvey, the youngest of the Chickering brothers, lived close by, at 133 West Chester Park, along the northern mall that led to the square – just around the corner from the factory, and one block from his mother’s home, at 29 Chester Square.

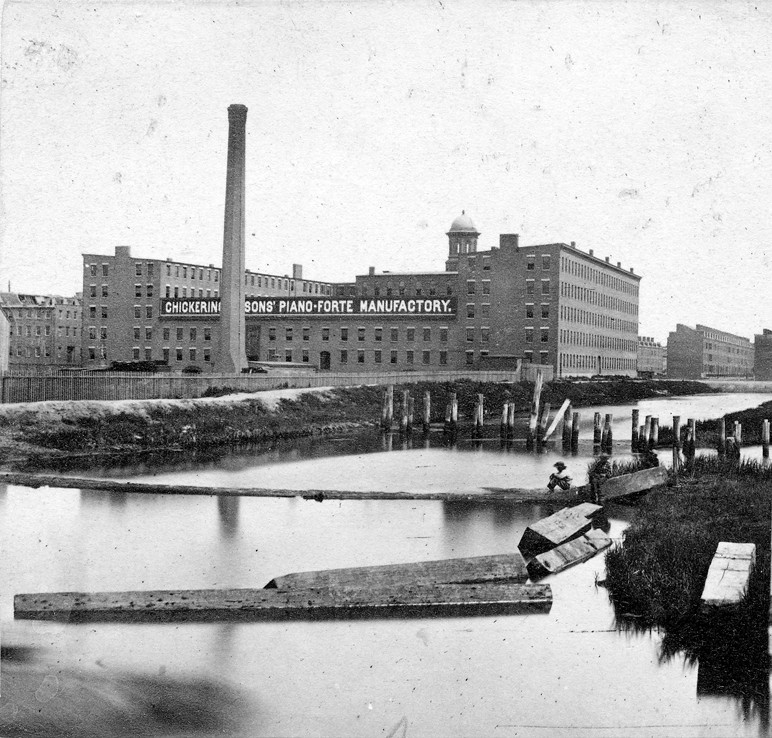

The new monolithic factory, whose address was 791 Tremont Street, was the largest building in the United States at the time, and featured steam-power engines and the latest technological advances. It was designed by architect Edward Payson. To our modern sensibilities, the intrusion of such a huge structure, with its ninety-foot-tall smoking chimney in the middle of a luxurious residential neighborhood, may look inappropriate. It does especially in the context of the bare landscape of the South End: indeed the back of the building seems to be an unreasonable addition to a city’s urban development:

The rear of the Chickering Piano Factory, ca. 1855

Photograph taken from the Providence Railroad line, between Saint Botolph Street and Columbus Avenue

Courtesy of The Bostonian Society

Yet much of the land facing the back of the building had not been developed, or even filled (the illustration above shows Chester Square in the distance, and large bodies of water at the edge of the factory’s perimeter, as the filling of the marshes was still under way), and the openness of the landscape probably made the contrast starker than it had been anticipated. At any rate, much thought was given to the manner in which the façade would blend harmoniously into the architectural landscape of the square and its surroundings, and in the way the tall chimney in the back of the building would not be seen at street level, peeking above the rooftops of the square’s five-story townhouses.

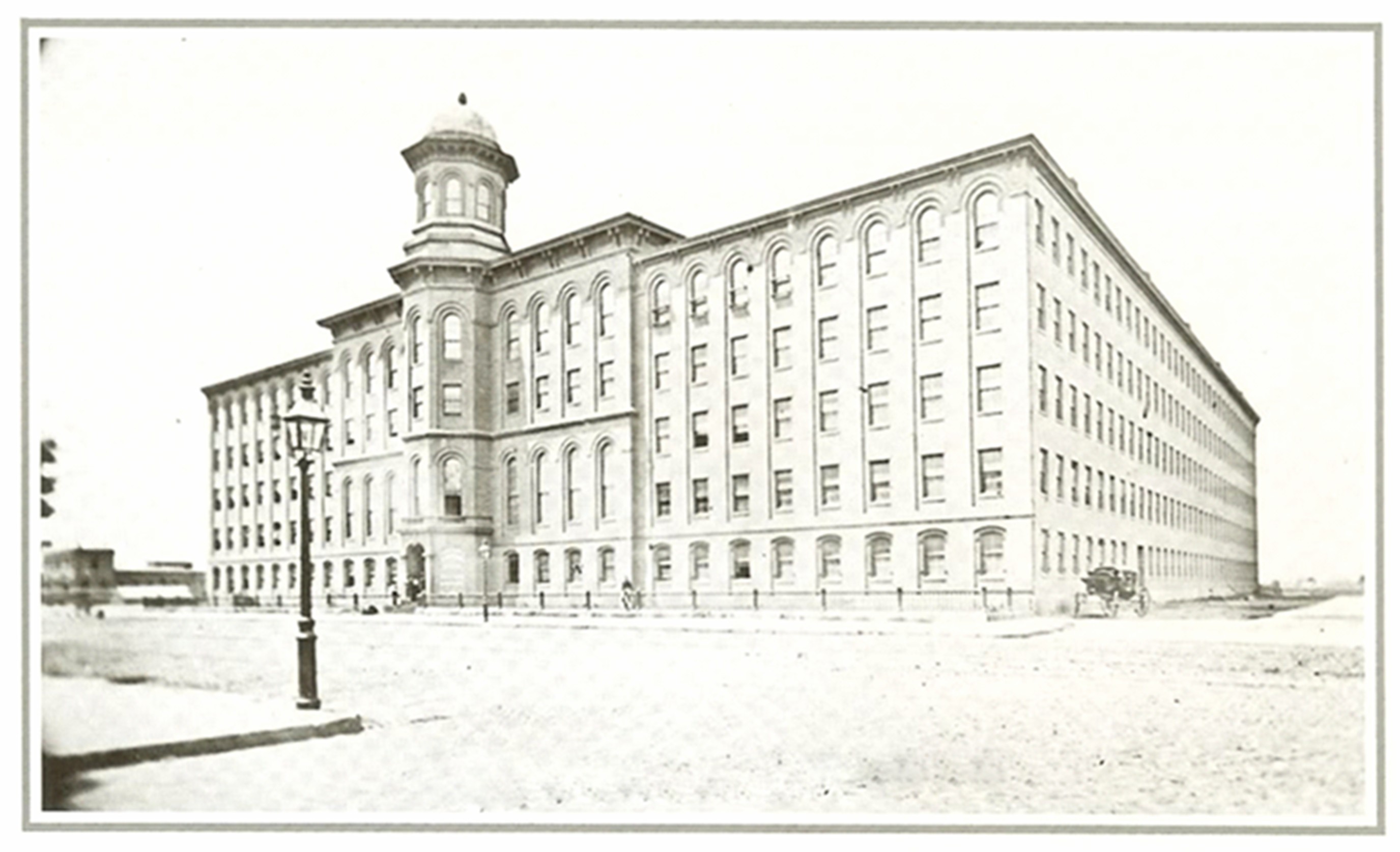

The façade of the Chickering Piano Factory at 791 Tremont Street

Photograph taken from the corner of Northampton and Tremont Streets, one short block south of Chester Square

(private collection)

A handsome lithograph of the Chickering Piano Factory, ca. 1870

Today, no city planning would allow a factory to be introduced in the fabric of its urban development; and perhaps for that very reason, no factory would be built with such consideration for its architectural attractiveness. The imposing façade remains as a nostalgic figure, next to more modern buildings and a gas station.

Named colloquially “The Piano Factory,” in 1972 the building was converted to artists’ studios, galleries, and residencies. Its history transcends piano making: during the Civil War, part of the building became the temporary home of the Spencer Repeating Rifle Company, which produced over eleven thousand of the rifles used on the battlefield.